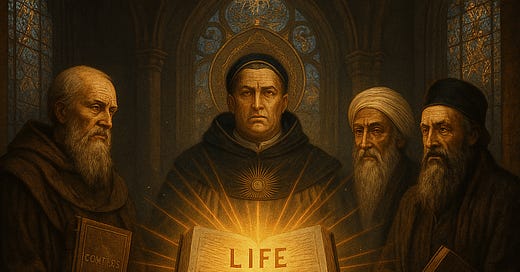

Thinkers

Augustine · Aquinas · Ibn Arabi · Luria

Signal

God = Good = Order = Life - but veiled in metaphysics, hierarchy, and obedience.

Interpretation

Medieval theology was the apex of pre-modern thought - a total integration of existence, value, and order into a single divine frame. In the West and across the Abrahamic world, it presented a vision of the cosmos in which all things had meaning because all things flowed from God. Reality was not chaotic; it was ordered, purposeful, and moral. To live rightly was to conform to the structure of creation - because creation was good.

This intuition - that life is good because it is rooted in the divine - formed the beating heart of medieval philosophy and mysticism. Whether through law, love, or light, the spiritual systems of the era all pointed toward the same conclusion: existence is not neutral or nihilistic. It is sacred. It is ordered. It is for something.

But that truth was never spoken plainly. It was encoded - veiled beneath layers of metaphysics, tradition, and institutional control. Meaning was not discovered through experience, but handed down through authority. Revelation became regulation.

And though the light was real, it came refracted through hierarchy. Insight hardened into orthodoxy. Systems that once shimmered with transcendence grew ossified with time.

Key Ideas

Augustine’s City of God casts human history as a spiritual battle between two loves: the love of self leading to the earthly city, and the love of God leading to eternal life. Life’s meaning is secured only by anchoring it in divine will, not temporal success.

Aquinas brings Aristotelian rationalism into Christian theology, claiming that to exist is to participate in God’s order. Natural law reflects divine reason - so to act according to one’s nature is to act morally. Goodness becomes ontological: to be is to be good.

Ibn Arabi, the great Sufi metaphysician, sees all being as the self-disclosure of the Real (al-Ḥaqq). The cosmos is a mirror in which God contemplates Himself. Life is love: a ceaseless unfolding of divine desire to be known.

Luria, the mystic of Safed, teaches that creation begins with contraction (tzimtzum) and the shattering of vessels. Existence is broken light - fragments of the divine in exile. The task of humanity is tikkun, the restoration of coherence and meaning through righteous action.

All of these models grasp that life, order, and goodness are one - but they house this realisation in theological systems that demand submission rather than participation. The divine is true - but distant. Life is meaningful - but only if interpreted correctly. The truth is there - but must be mediated.

Limitation

Dogma replaces feedback. Systems that once emerged from lived wisdom now resist adaptation.

Sacred knowledge becomes gatekept. Mystical insights are preserved, but shrouded in secrecy, elite language, or institutional monopoly.

The frame becomes static. Instead of evolving with life’s unfolding needs, truth is fossilised into orthodoxy. Heresy is not deviation from life, but from decree.

Medieval theology held onto something precious: the conviction that existence is not indifferent, that there is a structure to flourishing. But it lacked the ability to test and adapt that insight in the face of new conditions. It encoded truth - but could not evolve it.

Key Texts

Confessions – Augustine

Summa Theologica – Thomas Aquinas

The Bezels of Wisdom – Ibn Arabi

The Zohar and Etz Chaim – Lurianic Kabbalah

Synthesis Link

Medieval theology intuitively knew that life was sacred. That to exist, to act, to love, to build - these were not arbitrary, but reflections of a deeper order. But it buried that insight beneath layers of unchallengeable authority.

Synthesis reveals the hidden engine beneath the sacred: the structure of life itself.

What was once expressed in divine language is now understood as evolutionary logic.

“If a system cannot evolve, it will be selected out.

Truth that resists change ceases to serve life.”

(Synthesis – Axiom 7: Beyond Dogma)

The mystical becomes intelligible.

The sacred becomes functional.

The divine becomes dynamic.

Synthesis does not discard the theological tradition - it fulfils it. It shows that what Aquinas called “natural law,” what Ibn Arabi called “divine names,” and what Luria saw in shevirah (shattering), are not poetic myths - they are structural realities, expressed through different languages.

Where theology once said “God is Good, therefore Life is Good,”

Synthesis clarifies: “Life is Good, therefore God was the name for Life.”